data analytics (DA)

What is data analytics (DA)?

Data analytics (DA) is the process of examining data sets to find trends and draw conclusions about the information they contain. Increasingly, data analytics is done with the help of specialized systems and software. Data analytics technologies and techniques are widely used in commercial industries to enable organizations to make more informed business decisions. Scientists and researchers also use data analytics tools to verify or disprove scientific models, theories and hypotheses.

As a term, data analytics predominantly refers to an assortment of applications, from basic business intelligence (BI), reporting and online analytical processing to various forms of advanced analytics. In that sense, it's similar to business analytics, another umbrella term for approaches to analyzing data. The difference is that the latter is oriented to business uses, while data analytics has a broader focus. The expansive view of the term isn't universal, though. In some cases, people use data analytics specifically to mean advanced analytics, treating BI as a separate category.

Types of data analytics

Data analytics can be divided into the following four types:

- Descriptive analytics. Using historical data analysis, descriptive analytics aims to comprehend past events. It entails compiling data, identifying patterns and gaining insights into or learning from past events.

- Diagnostic analytics. Diagnostic analytics delves deeper into data to determine the reasons behind specific events. It involves identifying root causes, determining correlations and uncovering relationships between different variables.

- Predictive analytics. Predictive analytics forecasts future patterns or events using statistical algorithms and historical data. It attempts to forecast future events and evaluate the probability of various scenarios. Predictive analytics works with algorithms and methodologies such as linear regression or logistic regression models.

- Prescriptive analytics. Prescriptive analytics goes beyond predicting future outcomes to recommend specific actions for decision-making. It uses optimization and simulation techniques to determine the best course of action for desired outcomes.

Why is data analytics important?

Data analytics initiatives can help businesses increase revenue, improve operational efficiency, optimize marketing campaigns and bolster customer satisfaction efforts across multiple industries. It can also help organizations do the following:

- Personalize customer experiences. By going beyond traditional data methods, data analytics connects insights with actions, enabling businesses to create personalized customer experiences and develop related digital products.

- Predict future trends. By using predictive analysis technologies, businesses can create future-focused products and respond quickly to emerging market trends, thereby gaining a competitive advantage over business rivals. Depending on the application, the data that's analyzed can consist of either historical records or new information that has been processed for real-time analytics. In addition, it can come from a mix of internal systems and external data sources.

- Reduce operational costs. By optimizing processes and resource allocation, data analytics can help reduce unnecessary expenses and identify cost-saving opportunities within the organization.

- Provide risk management. Data analytics lets organizations identify and mitigate risks by detecting anomalies, fraud and potential compliance issues.

- Improve security. Companies use data analytics methods, such as parsing, analyzing and visualizing audit logs, to look at past security breaches and find the underlying vulnerabilities. Data analytics can also be integrated with monitoring and alerting systems to quickly notify security professionals in the event of a breach attempt.

- Measure performance. Data analytics provide organizations with metrics and key performance indicators (KPIs) to track progress, monitor performance and evaluate the success of business initiatives. This helps businesses respond promptly to changing market conditions and other operational challenges.

Data analytics applications

At a high level, data analytics methodologies and techniques include exploratory data analysis (EDA) and confirmatory data analysis (CDA). EDA aims to find patterns and relationships in data, while CDA applies statistical models and techniques to determine whether hypotheses about a data set are true or false. EDA is often compared to detective work, while CDA is akin to the work of a judge or jury during a court trial -- a distinction first drawn by statistician John W. Tukey in his 1977 book Exploratory Data Analysis.

Data analytics can also be separated into quantitative data analysis and qualitative data analysis. The former involves the analysis of numerical data with quantifiable variables. These variables can be compared or measured statistically. The qualitative approach is more interpretive, as it focuses on understanding the content of non-numerical data such as text, images, audio and video, as well as common phrases, themes and points of view.

Examples of data analytics applications that use these methodologies and approaches include the following:

- Business intelligence and reporting. At the application level, BI and reporting provide organizations with actionable information about KPIs, business operations, customers and more. In the past, data queries and reports were typically created for end users by BI developers who worked in IT. Now, more organizations use self-service BI tools that let executives, business analysts and operational workers run their own ad hoc queries and build reports themselves.

- Data mining. Advanced types of data analytics include data mining, which involves sorting through large data sets to identify trends, patterns and relationships.

- Retail. Data analytics can be used in the retail industry to forecast trends, launch new items and increase sales by understanding customer demands and purchasing patterns.

- Machine learning. ML can also be used for data analytics by running automated algorithms to churn through data sets more quickly than data scientists can do via conventional analytical modeling.

- Big data analytics. Big data analytics applies data mining, predictive analytics and ML tools to data sets that can include a mix of structured and unstructured data as well as semi-structured data. Text mining provides a means of analyzing documents, emails and other text-based content.

- Business uses. Data analytics initiatives support a wide variety of business uses. For example, banks and credit card companies analyze withdrawal and spending patterns for fraud detection and identity theft. E-commerce companies and marketing services providers use clickstream analysis to identify website visitors who are likely to buy a particular product or service based on navigation and page-viewing patterns. Healthcare organizations mine patient data to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments for cancer and other diseases.

- Churn forecast. Mobile network operators examine customer data to identify customers who are most likely to not come back and help organizations retain them.

- Marketing. Companies engage in customer relationship management analytics to segment customers for marketing campaigns and equip call center workers with up-to-date information about callers.

- Delivery logistics. Logistics companies such as UPS, DHL and FedEx use data analytics to improve delivery times, optimize operations and identify the most cost-effective shipping routes and modes of transportation.

- Government and public sector. Governments use data analytics for policy formation, resource distribution and for gaining insights into public needs and requirements.

Inside the data analytics process

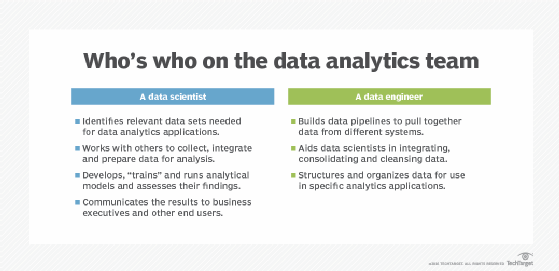

Data analytics applications involve more than just analyzing data, particularly for advanced analytics projects. Much of the required work happens upfront -- collecting, integrating and preparing data and then developing, testing and revising analytical models to ensure they produce accurate results. In addition to data scientists and other data analysts, analytics teams often include data engineers, who create data pipelines and help prepare data sets for analysis.

The following steps are involved in the data analytics process:

- Data collection. Data scientists identify the information they need for a particular analytics application and then work on their own or with data engineers and the IT staff to assemble it for use. Data from different source systems might need to be combined via data integration routines, transformed into a common format and loaded into an analytics system, such as a Hadoop cluster, NoSQL database or data warehouse. In other cases, the collection process might consist of pulling a relevant subset out of a stream of data that flows into Hadoop, for example. The data is then moved to a separate partition in the system so it can be analyzed without affecting the overall data set.

- Find and fix data quality problems. The analytics team must fix any problems that could affect the accuracy of analytics applications. This includes running data profiling and data cleansing tasks to ensure the information in a data set is consistent and that errors and duplicate entries are eliminated. Additional data preparation work is done to manipulate and organize the data for the planned analytics use.

- Apply data governance policies. Analytics teams apply data governance policies to ensure that the data follows corporate standards and is being used properly.

- Build an analytical model. An analytical model is built using predictive modeling tools or other analytics software and programming languages such as Python, Scala, R and Structured Query Language, i.e., SQL. Typically, the model is initially run against a partial data set to test its accuracy; it's then revised and tested again as needed. This process is known as training the model until it functions as intended.

- Run the production model. The model is run in production mode against the full data set once to address a specific information need or on an ongoing basis as the data is updated.

- Set a trigger. In some cases, analytics applications can be set to automatically trigger business actions. An example is stock trades by a financial services firm; when stocks hit a certain price, a trigger can activate to buy or sell them without human involvement.

- Communicate the results. The results generated by analytical models are communicated to business executives and other end users. Charts and other infographics can be designed to make findings easier to understand. Data visualizations, including charts and graphs, are often incorporated into BI dashboard applications that display data on a single screen and can be updated in real time as new information becomes available.

Can data analytics be automated?

Data analysts can automate processes to increase efficiency and quality. With automated data analytics, computer systems can carry out analytical operations with little assistance from humans. These techniques span the gamut of data modeling and statistical analysis, from simple scripts to sophisticated tools. For example, to support business choices, a cybersecurity organization might automate data collecting, web activity analysis and visualization.

Can data analytics be outsourced?

Third-party businesses or specialized service providers can be hired to handle data analytics tasks for various reasons, including cost-effectiveness, access to specialized expertise, scalability and flexibility as well as their expert knowledge of compliance policies. Outsourcing data analytics enables businesses to focus on their core activities while using external resources to handle data-related tasks efficiently.

Additionally, outsourcing can provide access to advanced analytics technologies and tools that might not be available in-house. However, it's essential for organizations to carefully consider factors such as data security, confidentiality and the reliability of the outsourcing partner before deciding to outsource data analytics functions.

Data analytics vs. big data analytics

Data analytics and big data analytics are related concepts with distinct meanings. As previously stated, data analytics is the process of analyzing raw data to extract meaningful insights from a given data set. While these strategies and tactics are frequently used with big data, they can also be applied to any type of data set, since data analytics is a broader term that encompasses all types of data analysis.

Examples of tools that are commonly used for data analysis include Amazon QuickSight, Apache Spark, Google Cloud streaming analytics, Python and Tableau.

Big data analyzes massive amounts of complex data that can't be examined with traditional data processing methods. It requires specialized tools for extracting meaningful insights from large amounts of structured, semi-structured and unstructured data typically stored in data lakes and data warehouses.

Amazon RedShift, Apache Hadoop, Google Cloud BigQuery and Microsoft Azure SQL Data Warehouse are examples of the options available for storing and processing big data.

Data analytics vs. data science

Unlike data analytics, data science isn't limited to a single function or field. It's a multidisciplinary field that combines deep learning, ML, artificial intelligence (AI), programming, math and statistics and scientific approaches to extract information from data.

As automation grows, data scientists focus more on business needs, strategic decisions and deep learning. Data analysts who work in BI will focus more on model creation and other routine tasks. In general, data scientists concentrate efforts on producing broad insights, while data analysts focus on answering specific questions. In terms of technical skills, future data scientists will need to focus more on the machine learning operations process, also called machine learning operations.

AI-enhanced predictive analytics tools are evolving and becoming easier to use. Discover several examples of predictive tools geared toward business users and data scientists.